الكرز: مهجة قحف

ترجمة

محمد بديع دك الباب

) مع تعديلات بسيطة من مهجة)

دمشق – سورية22/5/2011

رحلتُ عن سورية قبل سنين طويلة، طفلةً…

لكن سورية تذكرني:

أنا متأكدة من هذا.

لسورية مخدة صغيرة

إسمي مطرز عليها.

تحتفظ سورية لي ببعض الكرز

في إناء،

في آخر رف الثلاجة.

إتصلت بي، في نيسان الماضي، صديقة عادت لتوها من سورية

لتقول لي أنها حاولت أن تشتري كتاب شعر

من دكان كتب صغيرة في “السروجية”،

كتاباً حُشِرَ هناك في رف عالٍ تغطيه الغبار.

قال البائع:

“ليس بإمكانك الحصول على أي شيء من صف الكتب ذاك

هذه الكتب لمهجة، ابنة

منذر وميسون.”

أرأيتم؟ ستظل سورية تذكر

أطفالها الذين يعيشون عصر الرأسمالية الراحلة

في عصر معلومات بعيد.

بعض الناس يقولون إن سورية،

لو أني عدت إليها،

ستحدق في وجهي بالعدائية الكامنة بين محافظاتها.

بعضهم يقولون إن كل ما ستفعله سورية

هو أن تفرغ حافظة نقودي بكثرة لهاثها خلف الرشاوى

والشكوى من أسعار البطيخ

وحساب قيمة ساعة يدي وخاتمي

ثم سترميني في قسم المخابرات.

أنا على ثقة من أنني لو عدت إلى سورية،

فستصدح الموسيقا،

وستجري كل أحداث ميلودراما الفيلم الهندي:

ستعشقني الأرض

ستميل الأشجار نحوي مثل خالاتي وعماتي

وستحميني الجبال كأبناء عمومتي

ستقبل جبيني الكنائس القديمة

ستمسك بي المساجد وتأرجحني من على أقواسها

وتلف الكُنُسُ كتفيَّ بالبركات مثل الشال.

أنا متأكدة من أن بحرات البيوت سترش قدميّ بالماء،

مثل زميلات دراسة عرفنني منذ الصف الأول.

سيكون لكل صباح رائحة القهوة والهيل.

ولكل ساعة عصر نكهة الكزبرة والنعناع.

وستتمطى بمشيتها كل عشية كموسيقا العود.

سنتمدد كلنا على السطح تحت النجوم،

نأكل الجوز ونشرب الشاي في أكواب مزهرة صغيرة.

أنا متأكدة من أن دمشق ستقرقر بالنرجيلة

وتضحك ضحكتها الصاعدة من القلب مثل خال أو عم أمي أو أبي.

ستطلق حلب هديلها لي

مثل مؤذن وسيم أزرق العينين.

ستقطب حماة وتعاملني بتجهم

إنما برقة خفية تلوح على محياها.

ستضع حمص الأطباق البيضاوية الكبيرة

المليئة بالباذنجان المحشي والمثقلة باللوز

وتصحبني اللاذقية إلى شاطئ البحر

تقفز معي وتشتري لي الكرات البلاستيكية الكبيرة البهيجة.

أنا متأكدة من أن القرى ستُحني شعري

وتأخذني من يدي إلى عرس ابنتها في دير الزور.

ستحزم الغجريات وركيّ بوشاحهن

ويعزفن بآلات الكمان بأصواتها الحادة ويبرمنني دورات سريعة.

وسيرسل الشركس عريسا وسيما

يخطفني في عتمة الليل على خيول شديدة السواد

وُضِعَتْ عليها سُرُجٌ مزركشة ومزينة بالألوان الحمراء والذهبية.

سوف يثقب الكرد أذنيَّ بالكلمات الكردية الفضية.

سيطرز لي فلسطينيو سورية ثوباً

ويحزمون لي كتبي المدرسية في بقجة المدرسة.

وسيطلعني الدروز على أسرارٍ خفيةٍ

داخل معابد بيضاء صغيرة في قمم الجبال.

سيجلسني العلويون ويحكون لي

بأصوات خافتة حكايات قديمة مؤثرة

تناقلتها مئة من الأجيال.

ستختفي الأحقاد الطبقية والطائفية

وكذلك السجون السياسية وهروات التعذيب بالكهرباء

ولن يخشى أحد من أن يروه وهو يتحدث إلي

أو يصغي إلى شعر عن سورية.

هذه قصيدتي أنا وأستطيع أن أفعل بالعالم فيها ما أشاء.

يمكنني أن أصور مثل هذه الأشياء لأنني ظللت طيلة هذه السنين

أتتبع أولئك الناس والأماكن على خريطتي.

انظروا، هنا، على خريطة سورية التي أملكها.

لقد شحبت الألوان في مواضع طيّها

لأنني أحملها داخل جيب اسمه القلب.

(انتبهوا، لقد حذرتكم من أن هذه أحداث ميلودراما).

وستسير أحداث المسلسل هكذا: ستمثل سورية

دور امرأة مسكينة مع سيد قاسٍ لا يسمح لها بأن ترعاني

باعتباري طفلة تستحق أن تحظى بالرعاية.

ولا يسمح لها بأن تطعمني الكرز

وتلبسني الصوف الحلبي.

ولا يسمح لها بأن تشكل علي الحلي الذهبية الصغيرة

كي تحميني من أن تصيبني عين بأذى.

لذلك، كان عليها أن ترسل طفلتها بعيدا بعيدا

رغم أنني بكيت، وبكيتْ هي.

(كيف تنتهي هذه الأفلام المصرية عادة؟)

فإلى أين ذهبتُ؟

وما الذي صرتُ إليه؟

وهل أكلتُ الكرز في مقري الجديد؟

وهل دفئت كدفء الصوف الحلبي مع أسرتي التي تبنتني ؟

ماذا يحدث لطفلة لم تعد تستطيع أن تتكلم

لغة أمها؟

ماذا يحدث لعصفور لا يصبح بإمكانه أن يطير

في بيئته الطبيعية؟

ماذا يحدث لفتاة أرادت مرة أن تضع رأسها

على مخدة صغيرة اسمها مطرز عليها؟

قولوا لي من الذي أكل الكرز.

كان الكرز في وعاء صغير في آخر رف الثلاجة.

كان لي، فسورية تتذكر.

كنت

متأكدة من هذا.

The Cherries.

by Mohja Kahf

(1998)

I left Syria many years ago, as a child,

but Syria remembers me:

I am sure of it.

Syria keeps a small pillow

embroidered with my name.

Syria is saving some cherries

in a bowl for me,

at the back of the refrigerator.

Last April, a friend just back from Syria

phoned to say he’d tried to buy a book of poetry

in a small bookshop in Srujeh,

a book wedged high on a dusty shelf.

The shopkeeper said,

“You can’t have any from that stack;

they’re for Mohja, daughter

of Monzer and Maysoon.”

See? Syria still remembers

its children who live in late capitalism,

an information age away.

Some people say that Syria

would stare at me with provincial hostility

if I went back.

Some people say all Syria would do

is empty my wallet with demands for bribes,

complain about the price of melons,

calculate the value of my watch and ring,

and turn me in to the state police.

I am sure that if I went back to Syria,

there would be music,

and all the melodrama of a Hindi movie:

The ground would love me

The trees would lean toward me like aunts

The mountains would protect me like cousins

The ancient churches would kiss my forehead

The mosques would hold and rock me in their arches

The synagogues would lay blessings on my shoulders like a shawl.

I am sure the fountains would splash my feet with water,

like playmates who’ve known me since first grade.

Every morning would smell like coffee and cardamom.

Every afternoon would taste like coriander and mint.

Every evening would linger like the music of the oud.

We would all stretch out on the roof under the stars,

eating nuts and drinking tea in small flowered glasses.

I am sure Damascus would puff on a nargileh,

and laugh a deep laugh like a granduncle.

Aleppo would croon for me

like a handsome blue-eyed muezzin.

Hama would frown and act stern

but with a secret kindness on its brow.

Homs would set oval platters before me

of stuffed eggplants spilling over with almonds,

and Latakia would take me to the beach,

and skip with me and buy me big bright plastic balls.

I am sure the villages would soak my hair in henna

and lead me to their daughter’s wedding in Deir al-Zawr.

The gypsies would tie sashes around my hips

and play their squeaky violins and whirl me.

The Circassians would send a gorgeous bridegroom

to carry me away in dark of night on jet-black horses,

caparisoned and tassled red and gold.

The Kurds would pierce my ears with silver Kurdish words.

Syria’s Palestinians would embroider me a dress,

and tie my schoolbooks in a satchel.

The Druze would introduce me to esoteric mysteries

in small white mountaintop temples.

The Alawites would sit me down and tell me

old and powerful stories, handed down

in hushed voices by a hundred generations.

Hatreds based on class and sect would disappear,

along with political prisons and electric torture-prods,

and no one would be afraid to be seen talking to me,

or listening to poetry about Syria.

(This is my poem and I can do what I want

with the world in it.)

I can picture such things because all these years,

I have traced those people and places on my map.

See, here, on my map of Syria.

It’s faded where it’s been folded

because I carry it in a pocket called heart.

(Look, I told you this was melodrama.)

Here’s how the soap opera goes: Syria

plays a poor woman with a cruel master,

who wouldn’t let her care for me

as a child deserves to be cared for.

He wouldn’t let her feed me cherries

and dress me in Aleppan wool.

He wouldn’t let her pin little gold trinkets on me

to protect me from the evil eye.

So she had to send her child far away,

even though I cried and she cried.

(How do these Egyptian movies ever end?)

And where did I go?

And what did I become?

And in my new home did I eat cherries?

And in my adopted family was I warm like Aleppan wool?

What happens to a child who can no longer speak

the language of her mother?

What happens to a bird when it can no longer fly

in its natural habitat?

What happens to a girl who wanted once to put her head

on a small pillow embroidered with her name?

Tell me who ate the cherries.

They were in a small bowl in the back of the refrigerator.

They were for me, because Syria remembers.

I was

sure of it.

(

published in Mohja’s poetry book, Emails from Scheherazad, University Press of Florida, 2003

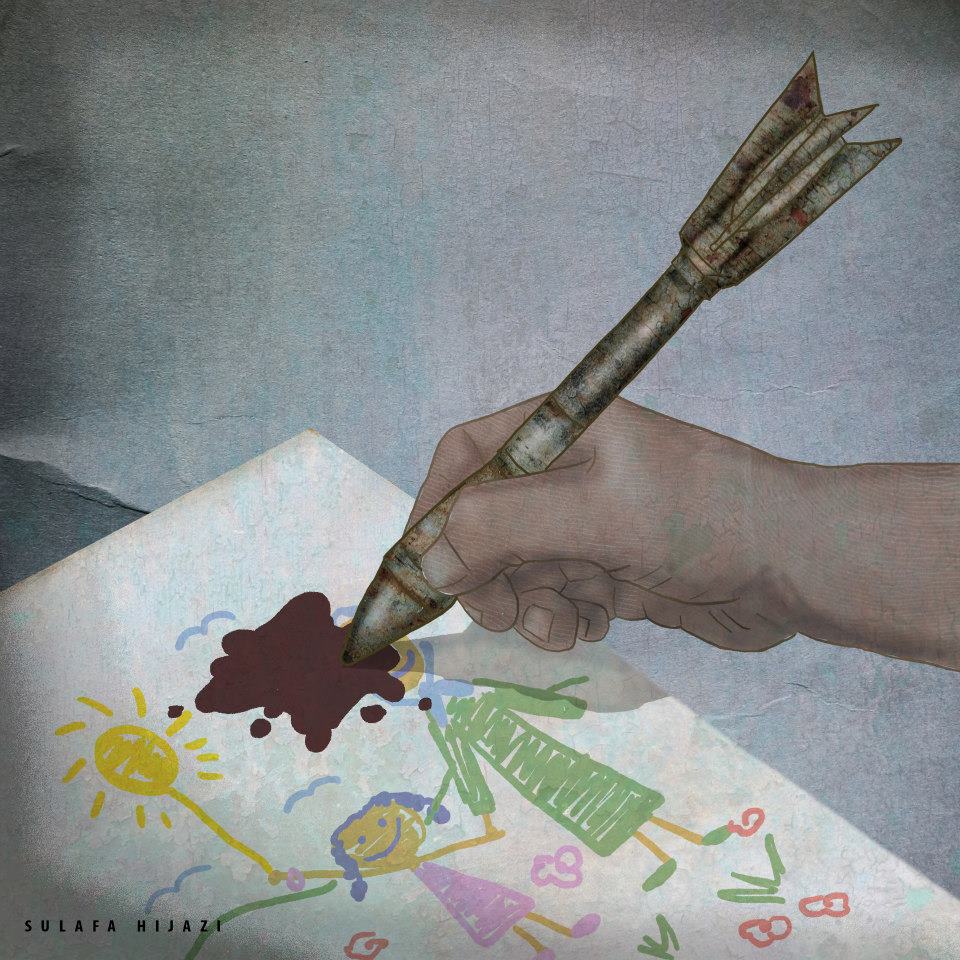

اللوحة للفنانة سلافة حجازي، وهي تشارك بلوحاتها في محور: بمثابة تحية إلى نساء سورية.

p align=”right”